Sixty-nine years ago, in Mexico City, a baby girl was born with a heart for horses and an unconquerable spirit. She wasn’t brought up around horses and had no relatives who owned horses. There wasn’t even a family friend who owned a horse, but not even that could stop her from pursuing her passion. Her name was Gretel Valdes.

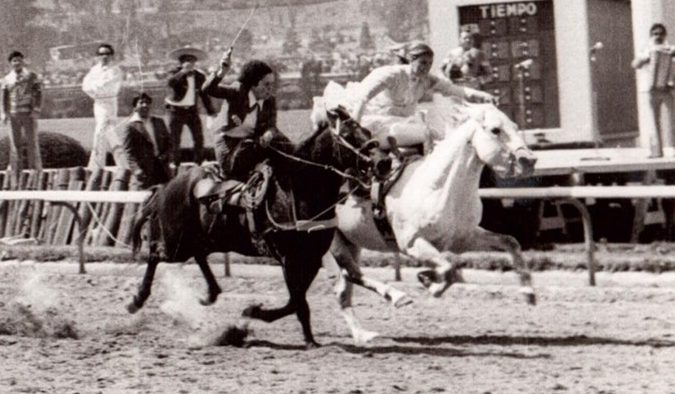

From early childhood, Valdes’s parents couldn’t help but notice her mysterious infatuation with horses. She was always trying to find a way to be taken to see a horse. Her first ride was on a pony at the Zoo in Mexico City. (PHOTO) The sight of a horse in a distant field as the family passed by in the car would send her into hysterics, so one day, her mother decided to make her dreams come true by taking her to a charreada, but little did she know that fate had much bigger plans for her daughter.

SIDE NOTE: Charrería is the official national sport of Mexico and is analogous to rodeo in the United States, albeit a much more stylized, artistic version. Focusing on competition between teams of riders, modern charreadas (rodeos) are normally held on Sundays and are a huge event in many smaller communities.

Originating with the arrival of horses from Spain in the 16th century, charrería has roots in the hacienda (ranch) culture of western Mexico in particular, although it enjoys nationwide popularity. In the beginning, charreadas (although they weren’t known as such then) took place between farm workers looking to show off their horse-riding and wrangling skills. However, with the Mexican Revolution in the early 20th century came the end of the hacienda and so the informal competitions between charros (riders) developed into formal charreadas and scored contests. By 1921, the National Charro Association had been established and in 1933, the presidential decree that declared charrería the national sport of Mexico was announced.

Modern charreadas feature a total of nine different skills events, known as suertes, and a female rider event called escaramuza, in which the charra rides sidesaddle and demonstrates her graceful equestrian ability. Judging is strict and competition is tough, especially given that both horses and riders often start training to compete in charrerías at the age of three. Speed, style, and precision are the orders of the day at these spectacular, traditional events.

Copied from https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/mexico/articles/a-guide-to-charreria-mexicos-national-sport/.

As the family entered the grounds of the event called the Nacional de Charros in Mexico City, the person at the gate told them to keep their tickets because there would be a raffle. Much to her supreme joy, the winning ticket was announced, and 12-year-old Valdes was holding it earning herself a horse and two months of classes at the riding school.

Valdes’s parents indulged her with the prize always thinking that she would soon tire of it, but as soon as the classes ended, her mother sold the horse and presented her with an ultimatum: she would no longer take her to the riding school for lessons, and if Gretel wanted to continue with her lessons, she would have to take a bus alone to the stable and back, 45 minutes one direction.

“I was twelve years old, and she thought that would end my passion,” Valdes mused. “You see, Mexico is not like in the U.S. The atmosphere was not very pleasant, and it was thought that equestrian sport could not be profitable enough to live decently by, but I took the bus. It never crossed my mind to stop riding.”

The riding school had lesson horses for students that didn’t have their own horses, so Valdes learned on a wide variety. She would often sit and watch the eight-person teams practicing their escaramuza routines, but inevitably, a girl would be absent making it difficult for the others to practice. The instructor began to ask Valdes to stand in for whichever girl was missing and she was assigned to that girl’s horse, so she quickly learned the positions of all the riders on all the teams and the nuances of riding each of their horses.

Valdes said, “When you don’t have a horse, and you have to ride any horse in any place, then you get better than the other ones if you want to do it.”

It wasn’t long before she was invited to attend a charreada as part of a team.

Again, Valdes’s mother wouldn’t take her to the competition, and she didn’t have the ornate, traditional dress to compete in; however, her grandmother made the dress, and Valdes, again, took the bus.

“It was the beginning of a predestined life to be. I never thought for a moment about leaving. Everything was growing up and learning in a very difficult world for women because Mexico at that time was a place of very macho men, and even more so in the equestrian world. I had to learn to survive in that environment and make a place for myself.”

As time went on, Valdes began to work in the industry, and earned the money to buy her own horse; however, her mother never attended an event. “When I was working for a place that puts on charreada’s as a horse trainer, I was to be given one of the biggest prizes in the charro industry for my work. My mother didn’t go because she hated that I was doing that. I didn’t feel sorry for myself, though. I was used to that.”

Although she may have sometimes felt so, Valdes was not alone. “When I was around 18 years old, Ing. Salvador Jiminez Cano was president of the Quarter Horse Breeders Association in Mexico. His wife and daughter loved horseback riding, so he helped me to be allowed to compete in calas (a bit like reining). When I competed, I was always the only woman who entered.

“The men didn’t want me to go in, but they had to do it. I was competing for the American Quarter Horse Association, and they don’t care if you are a girl or a boy.”

Valdes still rode in the women’s event, escaramuza, and sometimes competed in barrel racing as well. In February of 1979, when she was 25 years old, the first women’s horse race was organized at the Hipodromo de las Americas in Mexico City. She won it.

SIDE NOTE: Escaramuza is an important element of the role of Mexican woman. Having begun in 1953, when women began to take part in the all-men’s Charreria competitions. This event, steeped proudly in Mexican history, defies the cultural traditions of gender roles in Mexico. Women still ride sidesaddle as part of an all-female team, wearing the dazzling, traditional dresses and large sombreros of the time period it first began. The opening of each team’s run features the women running into the arena in formation at full speed. Just like in reining, there are large championships with attractive payouts.

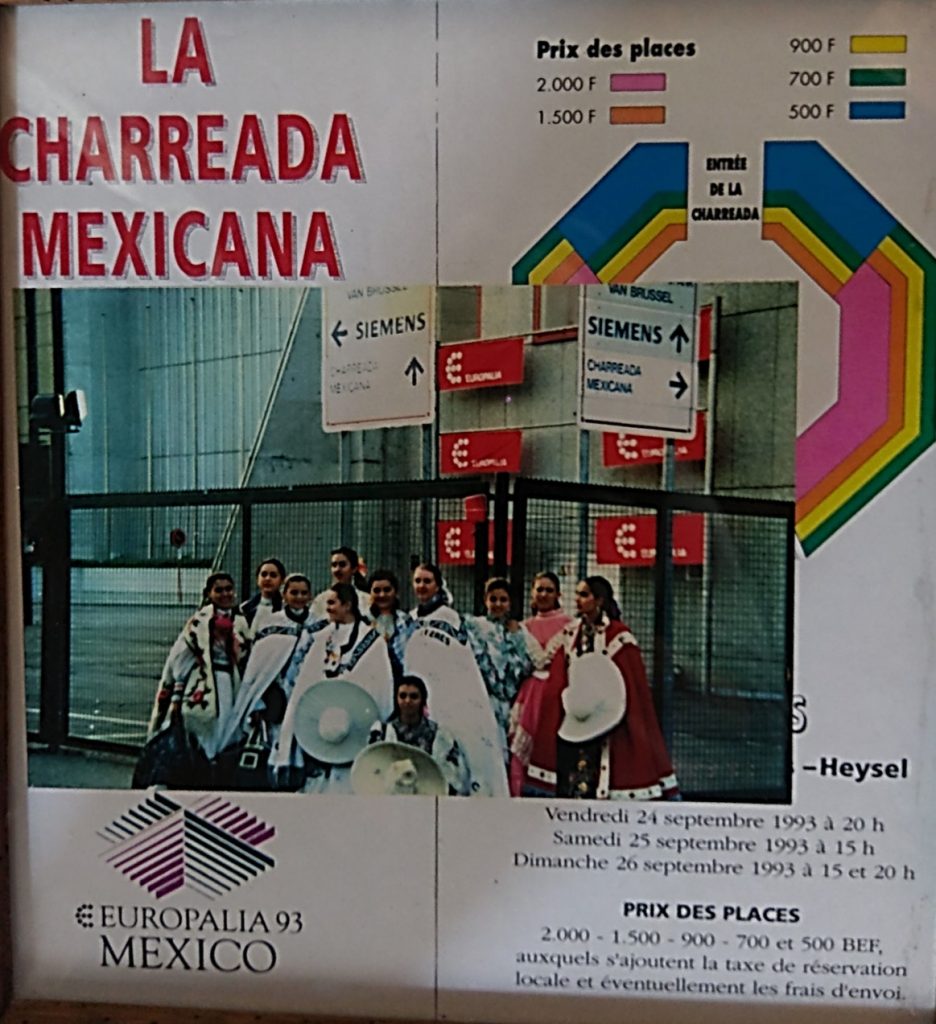

During her years in charreria, Valdes made her name known. She put together 6 different escaramuza teams, winning four national championships with them. For two years, she traveled with Antonio Aguilar and his teams of horses and mules as he became famous as “El Charro de Mexico” for popularizing the Mexican equestrian sport to international audiences. With him, Valdes was among those invited to the 1993 Europalia Arts Festival in Belgium to demonstrate the charreria style of riding. Every two years, Europalia officials invite a different country to come for fifteen days to demonstrate and display various elements of its culture: paintings, sports, performing arts, film, literature etc.

Valdes went many places with her team through the years, but over time, it began to wear on her. “I was tired. I was tired to be always with a team: eight girls,” she admitted. “With the girls, some of them can be very good riders, some of them are not. Some of them are very good sports, and they don’t whine and fight, but some of them just want to go and meet boys. It was very, very tiring, but suddenly, reining appears in my life!”

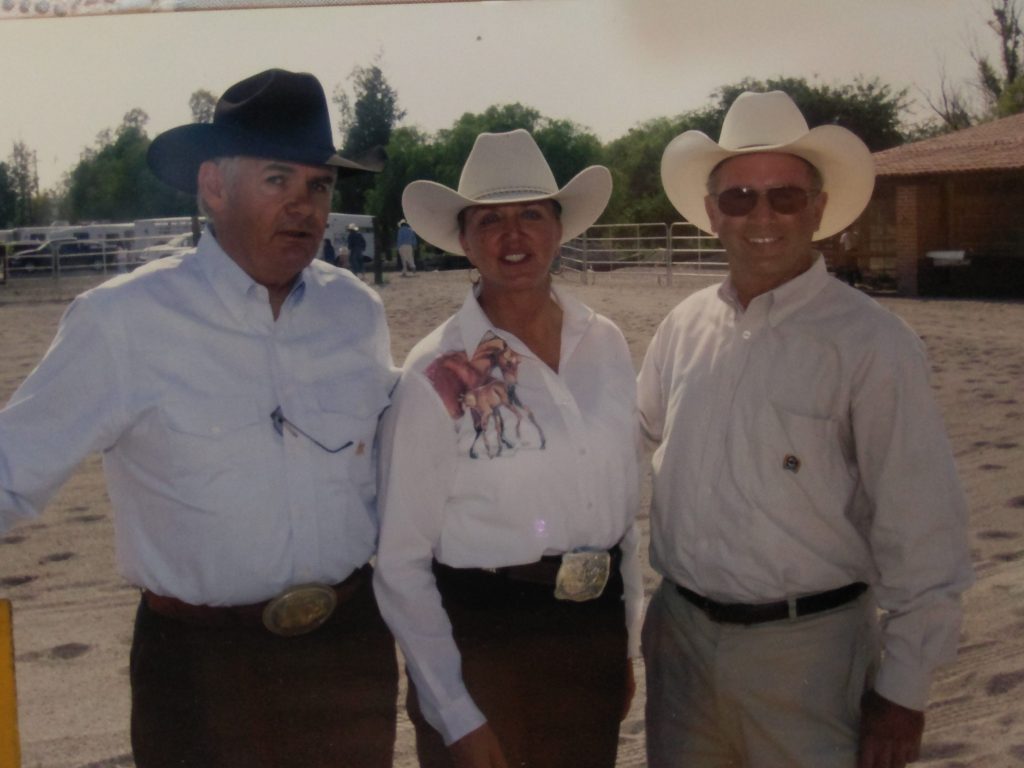

Valdes was invited to ride with Javier Alvarez Malo, a well-known charro rider who also was practicing reining. He began to teach her his reining techniques, and her life was forever changed. She was introduced to NRHA Judge and bit maker Greg Darnell, and he and Malo trained her in the arts of reining. “I said, ‘That’s what I want to do!’ because I can do it alone. I can do it all day or not,” she said. “At that time, I was 45 years old, and I had been side saddle all of my life. It was not an easy transition for me!

“Greg Darnall was my angel in Mexico! He has helped me with so much,” Valdes gushed. “I was shocked to know Greg Darnall in that time. He came to my ranch to see my horses, and I was so excited showing them to him that I fell down from my horse. It was so funny because I was laying down on the floor, and I saw the face of Greg Darnall and Malo staring at me on the floor. Malo said, ‘the shame!’ So that was my first contact with Greg Darnall, but now we are best friends for life because we have been traveling all around together.”

Malo organized the first reining competition in Mexico in 2000 with Darnall as the judge; however, all of the competitors had transitioned from Charreria, so they used charro saddles and outfits. Valdes wore a full-skirted dress, and men dressed in ornately embroidered outfits, all were topped with large sombreros. Valdes tied to win that show and refused a coin flip. She wanted to run it off which tipped the scale in her own favor. She, the only woman competing, won the class.

“I was always the only woman, everywhere! The males in Mexico are very macho, and they didn’t want to let me go in. I learned very quickly how to survive with all those guys and having blond hair and blue eyes…I had to fight very hard to survive. I had to be smart,” Valdes, whose father was German, shared. “It was very, very hard in that time, because men were the only ones competing, and they didn’t want women to be competing against them. If you, as a woman, won, they would be very mad!”

After her success at that first show, Valdes stopped competing in escaramuza, but remained in high demand to coach teams of girls in the event. Her program was never the same again, though, because she constantly tried to teach her students the methods she learned in reining.

“I have made so many escaramuza teams, they keep calling me to go with them,” Valdes said. “They started with me when they were little girls, and all of them are now mothers.”

After attending a couple more shows in Mexico, Valdes met Yvonne Mathieu, a Canadian reining trainer who was living in California. She asked him for reining lessons, and he agreed, but she would have to come to him in California.

Excited at the thought, Valdes hastily arranged her stay in California and began her lessons using horses in Mathieu’s barn. “I wasn’t sure who had it worse: them or me!” she said with a laugh. “He would say, ‘Why do you do that? Why are you doing that with your hands? Why do you hold the horse? Release your legs!’ I said, ‘I can’t! I was always shown to ride like that.’ Some days I would just cry so hard!”

Valdes’s indomitable spirit would not allow her to succumb to hardship. Just as in her childhood when she chose to ride the bus rather than consider giving up riding, she persevered without a thought to giving up. Quitting wasn’t in her nature.

While training with Mathieu, Valdes heard about the 2006 World Equestrian Games, hosted in Aachen, Germany, coming up, and set her sights upon it. She was told that she would have to go to two or three international competitions to earn the points for qualification, but because she didn’t have her own reining horse, she showed in the open. “I borrowed a horse there in California, and Yvonne said, ‘I’ll take you to Oklahoma, but the competition is in two days, and it takes two days to get there.’ We drove 26 hours nonstop to make it there. It was my first time in Oklahoma. It was so cold; I was shaking like crazy!” she remembered.

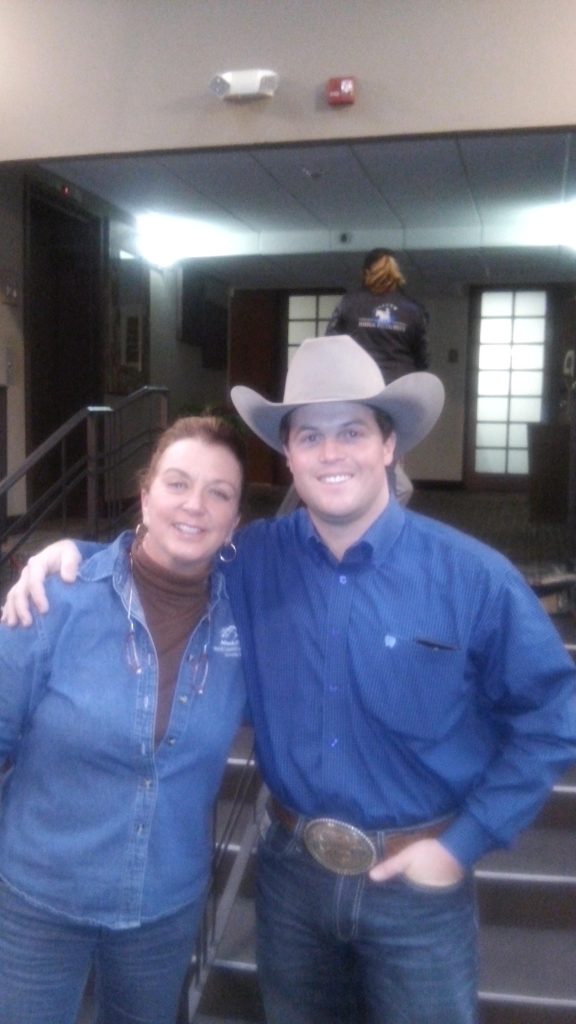

Valdes’s next international qualifier was held in Katy, Texas. As if by providence, Valdes met Casey Deary at that show and the two became fast friends, united by their love of horses and Deary’s love of her traditional Mexican cooking.

Deary learned of Valdes’s struggles and believed that he had the solution. “He said, ‘I will sell you a horse.’ I saw that horse competing the day we went to Oklahoma, and that horse was great! I was, at that time, in Mexico, training the daughters of Ismael Palacios. I told Casey, ‘I can’t buy a horse right now, but I will let you know how it is if we need a horse.’

“It was like a miracle! In that moment, Ismael said to me, ‘Hey, Gretel! Let’s buy a horse and compete in reining. So you can show my girls how to do it. If you see something good, buy that horse!’ I said, ‘Hey, Casey, come on, we will do it!’”

Valdes suggested to Palacios that they leave the horse in training with Casey so they would have one there to compete on when they go to the United States. He readily agreed. “In that moment, I left California. I told Casey that since he would have the horse to train, then I should go there for my lessons, too. That is how we did it. Casey would come to Mexico where he could eat authentic Mexican food, and I would go to Texas and ride horses, clean stalls, and cook.”

Eventually, Valdes had to bring her horses back to Mexico so Palacios’s daughters could learn to rein. Shying from the expense of carting them back to the United States to make her final international qualifier, Valdes teamed up with some other enthusiasts to organize their own qualifier in Mexico.

“We knew we would need to have an international judge. That wasn’t a problem because we had those. We had several international vets in Mexico, so that was not a problem either. The problem was the steward. We had a gentleman come from the U.S. and he gave classes and taught several men to be stewards, my husband is one, now too. We made a very good arena and invited Casey to compete. A Brazilian guy also came to compete. And I had my third qualifier.”

With Palacios’s help, Valdes purchased a second horse through Deary and found that she was more confident riding it, so she spoke to Palacios about taking it to Aachen. She shared, “He said, ‘Let’s do it! I’ll pay everything for the horse, and you pay for yourselves.’

“So I went to Aachen, but I went alone, only with my husband. I had no trainer, no chef d’quipe. The Mexican Federation was a little bit supportive of me. They came to watch my show but didn’t give me any money at all. Not one peso!”

“It was a great experience, though, to take the horse by plane and go from Mexico City, to Amersterdam, then to Belgium. I was competing with all the top guys from all over the world. I was by myself, but I don’t think I did so bad. I got a 70 from all of the judges.”

Valdes got back just in time for the FEI World Reining Masters competition in Oklahoma City, and because of the points she had collected to go to Aachen, she was able to compete there. She found herself, again, the only woman and the only representative of Mexico competing. “There were 18 competitors, and all of them so young, from the United States. There were others from France, Israel, Canada, from all over the world. It was really exciting.”

While Valdes was traveling the world competing, all of Mexico was watching. By the time another international qualifier was organized in Mexico in 2007, others were vying for the chance to follow in her footsteps. “All the guys were waking up in Mexico, because they were watching me competing everywhere. So they bought very good horses and they started to ride,” Valdes explained. “Greg Darnall started to help everybody to have good horses and good training.”

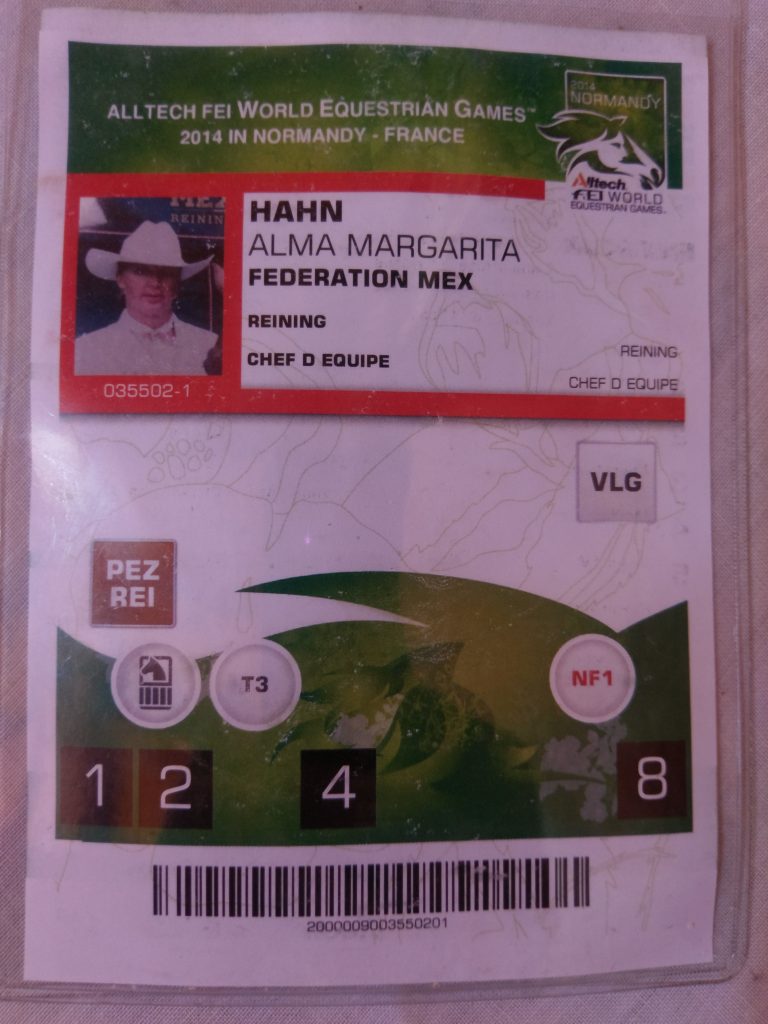

After tragedy struck for the owner of Valdes’s horses, she found herself afoot and unable to get another reining horse of the caliber she needed to be competitive, but her work was far from done. Because she had already mapped the course, she was asked to travel with the reining team to the 2010 World Equestrian Games in Lexington, Kentucky, and then again to Normandy, France in 2014 as chef d’equipe. She continues to be highly sought after to train girls in escaramuza competitions. For years, she was the only female charro, and she remains the only female NRHA Professional in Mexico.

“I have always had big angels in my life, and I am very grateful that I was able to make a path for other women in reining competition. Some people are born and die, and don’t leave anything behind. I have made a path for all the girls in the charro style. I was a beginner in making the regulations for girls in that. Right now, we are making a group for the girls who ride in the charro style. When you really make something in your life, you leave a path for other girls to follow so they can grow and compete and do things too. When you have things too easy, you don’t appreciate it. For me, it is important that the girls have things equal, like the guys, like in reining: Equal,” Valdes shared.